Celiac disease is a severe autoimmune disorder that affects millions of people worldwide, triggered by the ingestion of gluten. Gluten is a protein found in wheat, barley, and rye that can cause damage to the lining of the small intestine, leading to a range of symptoms like abdominal pain, diarrhea, fatigue, and malnutrition. While the disease has been known for centuries, the exact causes and mechanisms of celiac disease are still being studied.

Studies suggest that celiac disease is a genetic condition that runs in families, and people with specific genes are more susceptible to developing the disorder. However, not everyone with these genes will go on to develop celiac disease, indicating the role of environmental factors. The current scientific consensus is that celiac disease is triggered by a combination of genetic predisposition and environmental exposure.

The exact mechanisms of how environmental factors trigger celiac disease are still being studied, but researchers believe that the composition of the microbiome is a key factor. Exposure to certain viruses, infections, or antibiotics during early childhood can disrupt the delicate balance of the microbiome and trigger an immune response that targets gluten. Other research has pointed to the role of non-gluten proteins in wheat, or to environmental toxins like pesticides and pollutants.

Celiac disease can be diagnosed through blood tests and biopsies, but the only treatment is a strict gluten-free diet. This means avoiding all foods that contain gluten, including wheat, barley, rye, and some oats. However, with careful planning and creative substitutions, it is possible to enjoy a diverse and delicious diet without gluten.

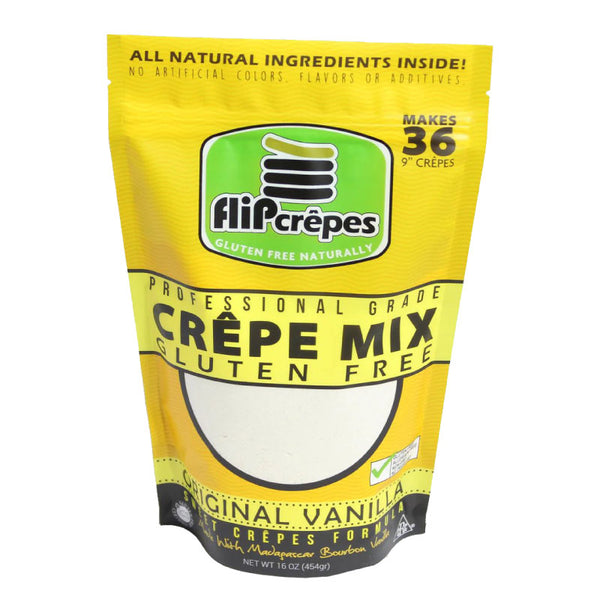

As awareness of celiac disease grows, more and more people are seeking out gluten-free alternatives to traditional wheat-based foods like bread, pasta, and crêpes. By understanding the origins and implications of celiac disease, we can better appreciate the importance of a healthy gut and the role that food plays in our lives.

References:

- Catassi C, Fasano A. Celiac disease diagnosis: simple rules are better than complicated algorithms. Am J Med. 2010 Mar;123(3):691-3. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.11.026. PMID: 20303299.

- Fasano A, Catassi C. Celiac disease. N Engl J Med. 2012 Jun 21;367(25):2419-26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1113994. PMID: 23252527.

- Lebwohl B, Ludvigsson JF, Green PHR. Celiac disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity. BMJ. 2015 Jun 23;351:h4347. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4347. PMID: 26109578.

- Sellitto M, Bai G, Serena G, et al. Proof of concept of microbiome-metabolome analysis and delayed gluten exposure on celiac disease autoimmunity in genetically at-risk infants. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33387. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033387. PMID: 22428087.

- Singh P, Arora A, Strand TA, Leffler DA, Catassi C, Green PHR, Kelly CP, Ahuja V. Global Prevalence of Celiac Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Jan;16(2):145-153.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.06.037. Epub 2017 Jul 7.